The word "gospel" means "good news". In Christianity, we believe in, study, proclaim, and celebrate the gospel. But although it is good news, that doesn't mean the opposite is true: just because something could be considered "good news" doesn't mean it is the gospel, or related to the gospel.

That's where I think we get stuck sometimes. We assume that if it's good news for us, it must be something God wants, too - maybe that it's part of even God's will, and God's priority, and God's purpose for our lives.

For instance, it might be good news - great news - to hear that your kid got straight A's, or that you're getting a raise or promotion at work, or that your car doesn't need major repairs after all. It might be good news that it won't rain on your wedding day, or that everyone will make it to the family reunion, or that there's enough butter left in the fridge so you don't have to make a trip to the store. But none of these have much of anything to do with the "good news" that is the Christian gospel.

Last week I wrote about Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, which is one

research team's attempt to boil down the religious views of the average

American teenager into one coherent set of beliefs. MTD makes this very

mistake, placing people and their desires and happiness at the center of

the universe and using God as a supernatural help to attain human

success and comfort.

So, what is this Christian "gospel"?

1. It is the good news about Jesus Christ (see Mark 1:1).

2. It is spiritual in nature; it deals with spiritual things and spiritual relationships. Paul said he became a "father" to the Corinthians "through the gospel" (1 Cor. 4:15).

3. It has the force of truth, and its essence is worth contending for (Galatians 2:5).

4. It brings people who are "out", "in"; it shows no favoritism; it is for everyone (Ephesians 3:6).

5. It's the answer to a mystery: how could God bring sinners into his adopted family? (Eph. 3:6, 6:19)

6. It is tied to a mission (Philippians 1:12).

7. Because it's a shared mission, the gospel promotes and requires unity (Philippians 1:27).

8. It is the message that through the death of Jesus, God has made a way for sinful, broken people to be reconciled to himself (Colossians 1:21-23).

9. It is the overcoming and defeat of death, and the attainment of immortality (2 Timothy 1:8-11).

10. Paul was imprisoned for it (Philemon 1:10-14).

The gospel is life-changing and life-giving. And, in many ways, it is unbelievable. Which is why we have to fight for it, and not let it be diminished by all of the other "good news" we look forward to hearing. Those things might be good news, but they're not the good news. In coming weeks I'll detail some messages that get offered as substitutes for the real good news.

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Thursday, February 19, 2015

The New American Religion

Ben Franklin wrote, "Half the truth is often a great lie." Indeed, you can learn a lot from half-truths, both from what is included and what is left out - as long as you're aware you're only getting half the truth!

Between 2001 and 2006, the National Study of Youth and Religion conducted the largest study ever of teenagers and their religious beliefs. One of its findings was that while 85 percent of American teens said they believed in God, less than a third were active in a congregation. Before you heave a sigh of relief ("At least most of them believe in God"), consider the content of those beliefs. What the survey revealed was dismal.

The average American teenager (at least in 2005) possessed a set of beliefs that were a watered-down mixture of self-help, deism, and works righteousness. The research team said it was as if they conceived of God as part-cosmic butler, part-therapist. Taking into account all of the teens they'd surveyed and distilling their beliefs down to a prominent core, some themes emerged:

The subject came up in our Wednesday night class on why the Millennial Generation is leaving churches. Some class members noted that it's a self-focused theology - life is about me, and God's job is to be there for me - and that perhaps not until kids grow up and out of a "me first" ethic can they move past a selfish belief in God. Fair point. The trouble is, there's just enough truth in Moralistic Therapeutic Deism to make it believable.

For instance, #1 is certainly true. God's existence is a bedrock belief of the Christian faith. #2 is also true - but there are a number of caveats. Us being good and nice isn't all that God wants, nor is it the central teaching of "most world religions". And, what about sin? How does that affect our ability to carry out the whole good, nice, and fair thing?

Is #3 true? While there's a certain amount of truth to the idea that being a Christian will bring you joy and feelings of peace and contentment, it does not follow that any means I might use to make myself feel good or experience joy are legitimate or part of God's plan. Endless trips to Disneyland might make me feel good. A life spared from family tragedy would make me happy. Becoming rich or famous or successful might produce feelings of accomplishment and self-worth. But that doesn't mean God is necessarily behind any of those things.

#4 reflects an attitude we're all perhaps guilty of sometimes. "God - bail me out!" means we expect God to always be faithful, even when we've been unfaithful. And 2 Timothy 2 affirms that God cannot be unfaithful, or he would be denying his character. But it betrays an attitude that says, "My life should be good. I deserve it. I should be successful, happy, and healthy. If I'm not, God ought to fix it." No theology of suffering. No learning or being shaped by trials. No "take up your cross and follow me". #4 is the credo of consumerist Christianity.

And #5 reflects the pop-religion dogma that will. not. die: Karma. It's an incredibly slippery concept that seems charitable, but really, would you want to be judged by a "good enough" standard once you die? What if what you thought all your life was good enough, wasn't?

Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is easy to believe. But it also easily fails. Lives are filled with hardship. God has a unique plan for solving the human predicament. But he's at the center of that plan, not you. MTD casts God as a piece within an individual's story, rather than seeing people as pieces fitting into God's story. It fits with a consumerist lifestyle that pursues personal comfort and pleasure above all things. But those are dreams uniquely fitted to our time and culture. Most of the world doesn't have the luxury of viewing God in this light. And if the self-centered gist of MTD is not universally true, to all people of all cultures, it's not true at all.

To think about: It's likely that none of the ideas of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism are taught to kids overtly: "Believe this." Instead, kids absorb it from the messages they receive - from parents, friends, the culture, even the church. What are the sources that fuel these beliefs?

Between 2001 and 2006, the National Study of Youth and Religion conducted the largest study ever of teenagers and their religious beliefs. One of its findings was that while 85 percent of American teens said they believed in God, less than a third were active in a congregation. Before you heave a sigh of relief ("At least most of them believe in God"), consider the content of those beliefs. What the survey revealed was dismal.

The average American teenager (at least in 2005) possessed a set of beliefs that were a watered-down mixture of self-help, deism, and works righteousness. The research team said it was as if they conceived of God as part-cosmic butler, part-therapist. Taking into account all of the teens they'd surveyed and distilling their beliefs down to a prominent core, some themes emerged:

- A God exists who created the world and watches over human life on earth.

- God wants people to be good, nice, and fair to each other, as taught in the Bible and by most world religions.

- The central goal of life is to be happy and feel good about oneself.

- God does not need to be particularly involved in one’s life except when God is needed to resolve a problem.

- Good people go to heaven when they die.

The subject came up in our Wednesday night class on why the Millennial Generation is leaving churches. Some class members noted that it's a self-focused theology - life is about me, and God's job is to be there for me - and that perhaps not until kids grow up and out of a "me first" ethic can they move past a selfish belief in God. Fair point. The trouble is, there's just enough truth in Moralistic Therapeutic Deism to make it believable.

For instance, #1 is certainly true. God's existence is a bedrock belief of the Christian faith. #2 is also true - but there are a number of caveats. Us being good and nice isn't all that God wants, nor is it the central teaching of "most world religions". And, what about sin? How does that affect our ability to carry out the whole good, nice, and fair thing?

Is #3 true? While there's a certain amount of truth to the idea that being a Christian will bring you joy and feelings of peace and contentment, it does not follow that any means I might use to make myself feel good or experience joy are legitimate or part of God's plan. Endless trips to Disneyland might make me feel good. A life spared from family tragedy would make me happy. Becoming rich or famous or successful might produce feelings of accomplishment and self-worth. But that doesn't mean God is necessarily behind any of those things.

#4 reflects an attitude we're all perhaps guilty of sometimes. "God - bail me out!" means we expect God to always be faithful, even when we've been unfaithful. And 2 Timothy 2 affirms that God cannot be unfaithful, or he would be denying his character. But it betrays an attitude that says, "My life should be good. I deserve it. I should be successful, happy, and healthy. If I'm not, God ought to fix it." No theology of suffering. No learning or being shaped by trials. No "take up your cross and follow me". #4 is the credo of consumerist Christianity.

And #5 reflects the pop-religion dogma that will. not. die: Karma. It's an incredibly slippery concept that seems charitable, but really, would you want to be judged by a "good enough" standard once you die? What if what you thought all your life was good enough, wasn't?

Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is easy to believe. But it also easily fails. Lives are filled with hardship. God has a unique plan for solving the human predicament. But he's at the center of that plan, not you. MTD casts God as a piece within an individual's story, rather than seeing people as pieces fitting into God's story. It fits with a consumerist lifestyle that pursues personal comfort and pleasure above all things. But those are dreams uniquely fitted to our time and culture. Most of the world doesn't have the luxury of viewing God in this light. And if the self-centered gist of MTD is not universally true, to all people of all cultures, it's not true at all.

To think about: It's likely that none of the ideas of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism are taught to kids overtly: "Believe this." Instead, kids absorb it from the messages they receive - from parents, friends, the culture, even the church. What are the sources that fuel these beliefs?

Monday, February 16, 2015

There are no winners and losers in church

My worst subject in school was probably PE. I was curious and liked to read, so the demands of a traditional classroom played to my strengths. But I could - and did - make all kinds of excuses why I didn't do well in PE: I was shorter than other kids, we weren't playing my favorite games (i.e., the ones I was sure I could win at), I always ended up on the weaker team, and that old childhood standby - "the other team cheated".

Truth is, I was a sore loser. And because of that, I came to dread and resent PE. But years later I came to understand the real reason I wasn't a star when it came to PE: I completely misunderstood the point of physical education itself. Turns out it's not to become a star athlete, nor to win, but to develop an appreciation for exercise and how to use your body.

To be fair, I don't think most kids understood the point of PE either, which is why it always threatened to devolve, particularly in Junior High, into a survival-of-the-fittest melee. But it wasn't for lack of trying. Our elementary PE teacher, Mr. Fritel, ran a tight ship and methodically planned games and exercises for us designed to develop hand-eye coordination, build muscle strength, gross motor skills, etc. - everything that a good physical education program should do. He taught us how to juggle, how to climb ropes, and how to jump. He started a jump rope show team that would practice before school and perform at basketball halftime shows. Some tricks were simple, and others impressive and complex, like jumping rope while belted to a pogo stick.

Still, all of this skill development, wonderful as it was, got eclipsed by competitiveness. As a result, I didn't want to play any sport that didn't come easy to me, because I might not win. Today, hyper-competitiveness also causes young athletes to drop out of sports they genuinely enjoy, just because they can't make "the cut". When a kid loves a sport, and then ends up turning away from that sport and from all sports in general, we have a problem.

Which brings us back to PE: its real purpose is not to delineate winners and losers, but to instill in kids a hopefully lifelong love of physical activity. Likewise, the real purpose of church for kids is to cultivate in them an excitement, a wonder, and a love for God. Simple as that. It's not to separate smart kids from non-smart kids, or to win attendance awards, or to be the fastest at finding Bible verses. If your church upbringing was filled with those things, let's be honest: some kids liked that stuff, but a lot of them hated it, too. And where are those adults now?

There are all kinds of reasons young adults walk away from churches. It isn't all the fault of unpleasant church experiences when they were kids. But some of it is, and some of it stems from our penchant for identifying "winners" and "losers" in church, when in fact, winning isn't the point at all. Competitiveness in church becomes a problem when it causes kids to think they aren't "good" at church, and when it whips kids into a frenzy that takes their eye far off the ball. No team or kid should get booed at church. But can we really blame kids for acting that way if we've cultivated a "just win, baby" ethic in church?

If kids grow up without exposure to physical activity, or if that activity is tainted by too much competitiveness (causing some to conclude, "I guess I'm just not good at this; it's not for me."), the habit of being active will not take root. In the same way, if church experiences aren't focused on enjoying God and the fellowship of other Christians (and discovering what there is about God that's actually enjoyable), those habits won't take root, either.

Truth is, I was a sore loser. And because of that, I came to dread and resent PE. But years later I came to understand the real reason I wasn't a star when it came to PE: I completely misunderstood the point of physical education itself. Turns out it's not to become a star athlete, nor to win, but to develop an appreciation for exercise and how to use your body.

To be fair, I don't think most kids understood the point of PE either, which is why it always threatened to devolve, particularly in Junior High, into a survival-of-the-fittest melee. But it wasn't for lack of trying. Our elementary PE teacher, Mr. Fritel, ran a tight ship and methodically planned games and exercises for us designed to develop hand-eye coordination, build muscle strength, gross motor skills, etc. - everything that a good physical education program should do. He taught us how to juggle, how to climb ropes, and how to jump. He started a jump rope show team that would practice before school and perform at basketball halftime shows. Some tricks were simple, and others impressive and complex, like jumping rope while belted to a pogo stick.

Still, all of this skill development, wonderful as it was, got eclipsed by competitiveness. As a result, I didn't want to play any sport that didn't come easy to me, because I might not win. Today, hyper-competitiveness also causes young athletes to drop out of sports they genuinely enjoy, just because they can't make "the cut". When a kid loves a sport, and then ends up turning away from that sport and from all sports in general, we have a problem.

Which brings us back to PE: its real purpose is not to delineate winners and losers, but to instill in kids a hopefully lifelong love of physical activity. Likewise, the real purpose of church for kids is to cultivate in them an excitement, a wonder, and a love for God. Simple as that. It's not to separate smart kids from non-smart kids, or to win attendance awards, or to be the fastest at finding Bible verses. If your church upbringing was filled with those things, let's be honest: some kids liked that stuff, but a lot of them hated it, too. And where are those adults now?

There are all kinds of reasons young adults walk away from churches. It isn't all the fault of unpleasant church experiences when they were kids. But some of it is, and some of it stems from our penchant for identifying "winners" and "losers" in church, when in fact, winning isn't the point at all. Competitiveness in church becomes a problem when it causes kids to think they aren't "good" at church, and when it whips kids into a frenzy that takes their eye far off the ball. No team or kid should get booed at church. But can we really blame kids for acting that way if we've cultivated a "just win, baby" ethic in church?

If kids grow up without exposure to physical activity, or if that activity is tainted by too much competitiveness (causing some to conclude, "I guess I'm just not good at this; it's not for me."), the habit of being active will not take root. In the same way, if church experiences aren't focused on enjoying God and the fellowship of other Christians (and discovering what there is about God that's actually enjoyable), those habits won't take root, either.

Monday, February 9, 2015

The Very Best Bible for your kid

I get asked often about Bibles for kids, and I'm glad. It's an easy question - and a hard one.

Want to know the very best Bible for your kid?

It's the one they'll read.

Seriously - that's the goal. That's the cardinal rule of Bible buying. The Bible your kid is drawn to, devours, dog-ears, marks up, can't wait to read - that's the one they need to have.

Which one that will be is a harder question, and you'll only know by exposing kids to lots of different ones. I'll make some suggestions at the end of this post, but a trip to a Christian bookstore with your kid is time well-spent. Better to buy them the one they pick out than surprise them with one that ends up sitting on the shelf.

Keeping in mind cardinal rule #1, here are a couple of other guidelines:

1. Don't judge the book by its cover. I can't tell you how many flashy, cool-looking covers I've seen, for every kind of kid imaginable - rough & tumble, brainy, girly-girl, athletic, adventurous - yet you open them up and it's no different a Bible than you'd find in a typical adult church. Which doesn't make it a bad choice, but if your kid would be unlikely to read the adult Bible from church, will a cool cover make them more likely to read a similar Bible at home? It might, but consider that carefully. Bible publishers design "kid Bibles" this way because their job is to sell Bibles, and there's nothing wrong with that, but putting neat-o packaging around it and slapping the words "Kid's Bible" or "for Kids" doesn't transform it into something that will be easily understood nor readily consumed by kids. And remember, that's the goal. The goal isn't just that they have a Bible they'll proudly claim and carry around, but that they'll use that Bible. Readability plays a big role in that. Which lead us to...

2. Pay attention to translations. The NIV, which is the preferred translation in many evangelical churches, has a 7th-grade reading level. In other words, someone who has completed 7th grade should be able to read and understand it. The King James Version? 12th grade (but, the New King James, 7th). The English Standard Version is at a 10th grade reading level, while the New Living Translation registers at a 6th grade reading level. (See more here.)

Why they wouldn't make all Bibles as easy to read as possible comes down to translation philosophy: are you trying to reproduce the words from the Greek and Hebrew, even if the reading comes out difficult and stilted, or are you trying to reproduce the ideas, even if that means you employ sentence construction and phrases that are easily understood, but not "literally" a translation of the manuscript? (Here's what John 3:16 looks like when Greek words are translated directly to English, with no regard for what makes "good" English: "Thus for loved God the world that the son the only-begotten he gave (so) that all believing in him not might perish but might have life eternal.") Naturally, because of cardinal rule #1 - the best Bible is the one your kid will read - I'm in favor of the second approach when it comes to Bibles for kids, because if they're confused and find the reading too difficult, they won't read it, and then what have you gained?

The "easiest" translations to read are the New International Reader's Version (NIrV), the New Century Version (NCV), and Contemporary English Version (CEV), all at a 3rd grade reading level. To get any simpler than that, you have to resort to translations-of-translations (the NIrV is one), which take English translations and make them even simpler. Many of these were developed for non-native English speakers. Which leads us to...

3. Bibles vs. Bible story books. Many kids' Bibles are in fact compilations of important Bible stories. Or more accurately - compilations of the accounts of important events that are recorded in the Bible. That's one weakness of Bible "storybooks", that they could give kids the impression that the Bible contains "stories" (that is, fiction). But that's easily overcome, by repeatedly emphasizing to kids that these are true stories involving people who really lived.

Another drawback is that while the stories are arranged chronologically, there's a jarring lack of continuity. Jesus might immediately follow after Daniel, despite the 600 years between them. But young kids have trouble conceptualizing vast amounts of time anyhow, and even an adult Bible omits hundreds of years - the Bible is not an comprehensive history of the human race.

Clearly, very young children will use storybook Bibles. But if you're anxious that your older child still hasn't "graduated" to a full, 66-book, chapter-and-verse Bible - don't be. Refer back to cardinal rule #1: the best Bible is the one your kid will read. The message of the Bible is what transforms us; not the particular words. When you read an English Bible, you're not getting the words, but an interpretation, communicating the meaning in the Greek and Hebrew.

And by the same token, don't stress out over Bible mechanics. Kids learn about the Bible's layout and how to navigate it as a byproduct of actually reading it. Find the one they love to read, and the rest will follow. Which leads us to...

4. Set a good example. This article stresses that a love of reading cannot be imposed on kids, but it may be contagious. Kids who read books tend to have parents who love to read. Likewise, if kids see us reading - and enjoying reading - the Bible, they might come to value it as well.

And I beg you: don't pay your kid to read the Bible. Let them develop it because it excites their imagination, satisfies their curiosity, and fills their soul. Rewards cheapen what the Bible is all about.

If you're a little lost when it comes to reading the Bible, we have a great class for you and your kid to take together once they've reached 4th grade. What's The Story? and What's This Book? are designed to promote Bible literacy and make you a good Bible reader. Look for their re-launch this spring once the new chapel opens.

A Couple of Recommendations

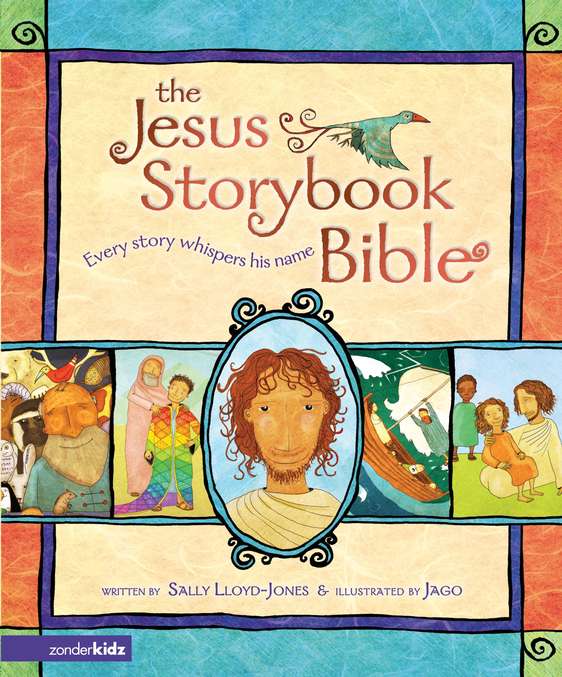

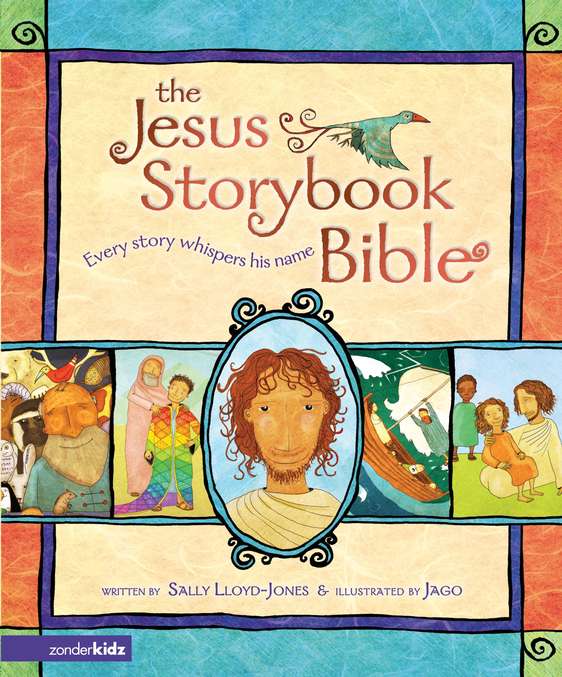

The Jesus Storybook Bible: Every Story Whispers His Name This awesome little innovation manages to weave Jesus into every selected Old Testament and New Testament story, so that while you may be learning about Noah, you're also learning about his connection to the savior who was to come. I haven't heard from any family yet that hasn't loved this Bible.

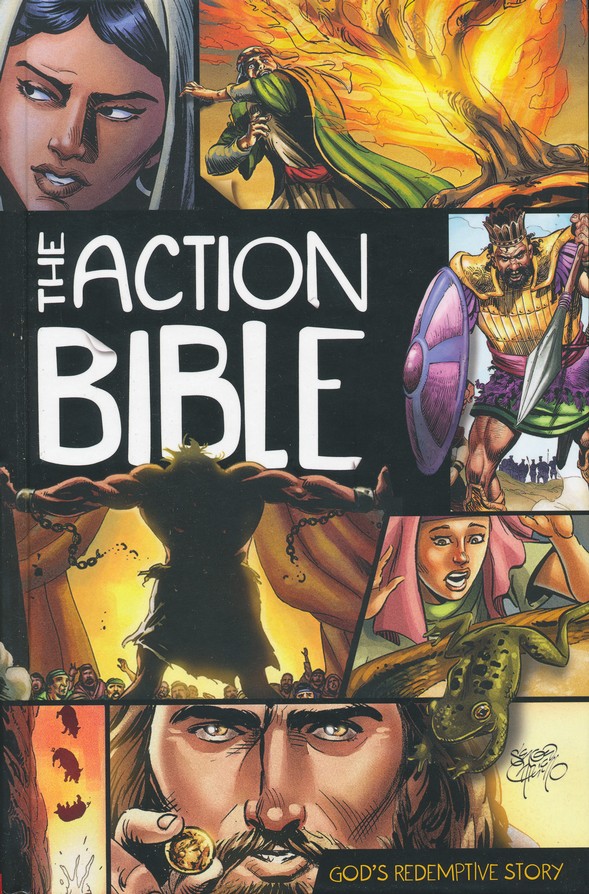

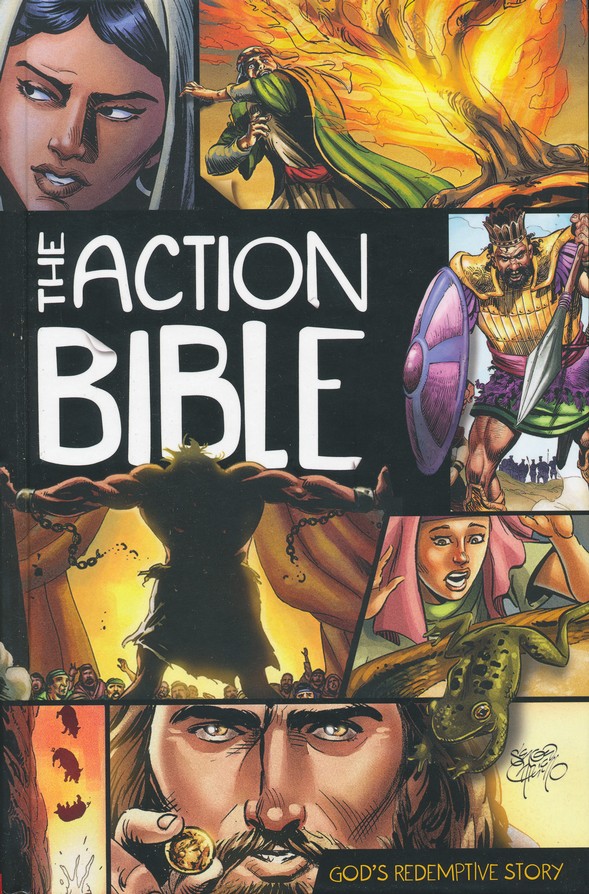

The Action Bible Kids have been fascinated with this one for a few years now. Full-color, impressive drawings, laid out comic book style, and again with a focus on the "big picture" story of the Bible and God's hand in sovereignly saving his people.

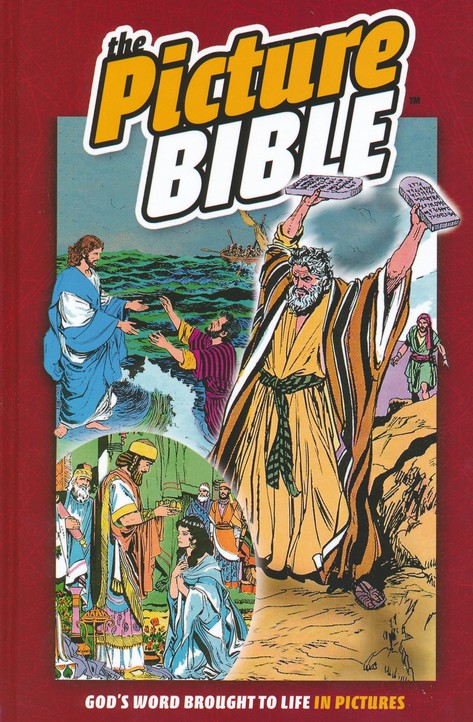

The Picture Bible is what the name suggests. It's very similar to the Action Bible in that it selects several characters and relates events from the life of each one, but the illustrations aren't as striking.

If you want a full-text, "regular" Bible, just take your kid online or to a Christian bookstore and have them choose the cover style that suits them. Unfortunately, the easier the reading level, the fewer the choices you'll have - most "kids' Bibles" tend to be NIV.

Want to know the very best Bible for your kid?

It's the one they'll read.

Seriously - that's the goal. That's the cardinal rule of Bible buying. The Bible your kid is drawn to, devours, dog-ears, marks up, can't wait to read - that's the one they need to have.

Which one that will be is a harder question, and you'll only know by exposing kids to lots of different ones. I'll make some suggestions at the end of this post, but a trip to a Christian bookstore with your kid is time well-spent. Better to buy them the one they pick out than surprise them with one that ends up sitting on the shelf.

Keeping in mind cardinal rule #1, here are a couple of other guidelines:

1. Don't judge the book by its cover. I can't tell you how many flashy, cool-looking covers I've seen, for every kind of kid imaginable - rough & tumble, brainy, girly-girl, athletic, adventurous - yet you open them up and it's no different a Bible than you'd find in a typical adult church. Which doesn't make it a bad choice, but if your kid would be unlikely to read the adult Bible from church, will a cool cover make them more likely to read a similar Bible at home? It might, but consider that carefully. Bible publishers design "kid Bibles" this way because their job is to sell Bibles, and there's nothing wrong with that, but putting neat-o packaging around it and slapping the words "Kid's Bible" or "for Kids" doesn't transform it into something that will be easily understood nor readily consumed by kids. And remember, that's the goal. The goal isn't just that they have a Bible they'll proudly claim and carry around, but that they'll use that Bible. Readability plays a big role in that. Which lead us to...

2. Pay attention to translations. The NIV, which is the preferred translation in many evangelical churches, has a 7th-grade reading level. In other words, someone who has completed 7th grade should be able to read and understand it. The King James Version? 12th grade (but, the New King James, 7th). The English Standard Version is at a 10th grade reading level, while the New Living Translation registers at a 6th grade reading level. (See more here.)

Why they wouldn't make all Bibles as easy to read as possible comes down to translation philosophy: are you trying to reproduce the words from the Greek and Hebrew, even if the reading comes out difficult and stilted, or are you trying to reproduce the ideas, even if that means you employ sentence construction and phrases that are easily understood, but not "literally" a translation of the manuscript? (Here's what John 3:16 looks like when Greek words are translated directly to English, with no regard for what makes "good" English: "Thus for loved God the world that the son the only-begotten he gave (so) that all believing in him not might perish but might have life eternal.") Naturally, because of cardinal rule #1 - the best Bible is the one your kid will read - I'm in favor of the second approach when it comes to Bibles for kids, because if they're confused and find the reading too difficult, they won't read it, and then what have you gained?

The "easiest" translations to read are the New International Reader's Version (NIrV), the New Century Version (NCV), and Contemporary English Version (CEV), all at a 3rd grade reading level. To get any simpler than that, you have to resort to translations-of-translations (the NIrV is one), which take English translations and make them even simpler. Many of these were developed for non-native English speakers. Which leads us to...

3. Bibles vs. Bible story books. Many kids' Bibles are in fact compilations of important Bible stories. Or more accurately - compilations of the accounts of important events that are recorded in the Bible. That's one weakness of Bible "storybooks", that they could give kids the impression that the Bible contains "stories" (that is, fiction). But that's easily overcome, by repeatedly emphasizing to kids that these are true stories involving people who really lived.

Another drawback is that while the stories are arranged chronologically, there's a jarring lack of continuity. Jesus might immediately follow after Daniel, despite the 600 years between them. But young kids have trouble conceptualizing vast amounts of time anyhow, and even an adult Bible omits hundreds of years - the Bible is not an comprehensive history of the human race.

Clearly, very young children will use storybook Bibles. But if you're anxious that your older child still hasn't "graduated" to a full, 66-book, chapter-and-verse Bible - don't be. Refer back to cardinal rule #1: the best Bible is the one your kid will read. The message of the Bible is what transforms us; not the particular words. When you read an English Bible, you're not getting the words, but an interpretation, communicating the meaning in the Greek and Hebrew.

And by the same token, don't stress out over Bible mechanics. Kids learn about the Bible's layout and how to navigate it as a byproduct of actually reading it. Find the one they love to read, and the rest will follow. Which leads us to...

4. Set a good example. This article stresses that a love of reading cannot be imposed on kids, but it may be contagious. Kids who read books tend to have parents who love to read. Likewise, if kids see us reading - and enjoying reading - the Bible, they might come to value it as well.

And I beg you: don't pay your kid to read the Bible. Let them develop it because it excites their imagination, satisfies their curiosity, and fills their soul. Rewards cheapen what the Bible is all about.

If you're a little lost when it comes to reading the Bible, we have a great class for you and your kid to take together once they've reached 4th grade. What's The Story? and What's This Book? are designed to promote Bible literacy and make you a good Bible reader. Look for their re-launch this spring once the new chapel opens.

A Couple of Recommendations

The Jesus Storybook Bible: Every Story Whispers His Name This awesome little innovation manages to weave Jesus into every selected Old Testament and New Testament story, so that while you may be learning about Noah, you're also learning about his connection to the savior who was to come. I haven't heard from any family yet that hasn't loved this Bible.

The Action Bible Kids have been fascinated with this one for a few years now. Full-color, impressive drawings, laid out comic book style, and again with a focus on the "big picture" story of the Bible and God's hand in sovereignly saving his people.

The Picture Bible is what the name suggests. It's very similar to the Action Bible in that it selects several characters and relates events from the life of each one, but the illustrations aren't as striking.

If you want a full-text, "regular" Bible, just take your kid online or to a Christian bookstore and have them choose the cover style that suits them. Unfortunately, the easier the reading level, the fewer the choices you'll have - most "kids' Bibles" tend to be NIV.

Sunday, February 1, 2015

The "Hug" of God

"I used to feel God's presence all around me," the caller said to me, "But lately I haven't felt it as much." As pastors, we get all kinds of questions; this one happened to come from someone who looked us up randomly and called (no joke), but it's a variation on something we all experience from time to time: why do we go through times that we don't feel close to God?

It was revealed a few years ago that even Mother Theresa, a beacon of faithfulness and self-sacrifice, went through a long period of questioning and doubt at mid-life, a "dark night of the soul" that didn't lift. Because of her sense of call, she soldiered on, and ultimately this perseverance led to a deeper identification with the suffering of the poor whom she served.

God's presence is a fact. Sometimes it is accompanied by a feeling. Jesus said, "Surely I am with you always, even to the end of the ages" and "Never will I leave you, nor forsake you". Numerous passages in the Psalms talk about God's omnipresence, and the fact that he goes before us and surrounds us with his presence. God is everywhere!

But we don't always feel it. So we have to trust what's true, and resist letting feelings of loneliness or despair be the measure of the strength of God's presence.

Think about a hug. A hug is a tangible expression of love and care. It reassures us, giving meaning to whatever words of adoration or appreciation accompany it. But hugs can't last forever. You can't hug your child all day long; but that doesn't mean your love ceases the moment the embrace is broken, nor that the love is stronger during the hug, nor that it wears off the longer they're away from you.

So it is with feeling God's presence. It's a nice reassurance, but its absence doesn't indicate a weakness of God's resolve. Certainly there are things we can do on our part to dull our receptiveness, and it's also God's prerogative to reveal himself however to whomever he wishes. But as we can see from the example of Mother Theresa, there is not a direct correlation between one's longing for God and their acute awareness of his presence.

As much as worship services, camps, and retreats try to push us toward them, it turns out that an authentic spiritual life is not an unbroken chain of mountaintop experiences. There are valleys, deserts, and long stretches of lonely highway.

One of the most confusing things about the Christian experience to kids is understanding what grown-ups mean when they say God talks to them or that they felt his presence. We would do well to couch the language of experience in this important caveat: it is not feeling his presence or hearing his voice that makes him real. Rather, God is real and present; and sometimes he chooses to reinforce this by making his presence especially known.

It was revealed a few years ago that even Mother Theresa, a beacon of faithfulness and self-sacrifice, went through a long period of questioning and doubt at mid-life, a "dark night of the soul" that didn't lift. Because of her sense of call, she soldiered on, and ultimately this perseverance led to a deeper identification with the suffering of the poor whom she served.

God's presence is a fact. Sometimes it is accompanied by a feeling. Jesus said, "Surely I am with you always, even to the end of the ages" and "Never will I leave you, nor forsake you". Numerous passages in the Psalms talk about God's omnipresence, and the fact that he goes before us and surrounds us with his presence. God is everywhere!

But we don't always feel it. So we have to trust what's true, and resist letting feelings of loneliness or despair be the measure of the strength of God's presence.

Think about a hug. A hug is a tangible expression of love and care. It reassures us, giving meaning to whatever words of adoration or appreciation accompany it. But hugs can't last forever. You can't hug your child all day long; but that doesn't mean your love ceases the moment the embrace is broken, nor that the love is stronger during the hug, nor that it wears off the longer they're away from you.

So it is with feeling God's presence. It's a nice reassurance, but its absence doesn't indicate a weakness of God's resolve. Certainly there are things we can do on our part to dull our receptiveness, and it's also God's prerogative to reveal himself however to whomever he wishes. But as we can see from the example of Mother Theresa, there is not a direct correlation between one's longing for God and their acute awareness of his presence.

As much as worship services, camps, and retreats try to push us toward them, it turns out that an authentic spiritual life is not an unbroken chain of mountaintop experiences. There are valleys, deserts, and long stretches of lonely highway.

One of the most confusing things about the Christian experience to kids is understanding what grown-ups mean when they say God talks to them or that they felt his presence. We would do well to couch the language of experience in this important caveat: it is not feeling his presence or hearing his voice that makes him real. Rather, God is real and present; and sometimes he chooses to reinforce this by making his presence especially known.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)